Looking at how the land inspires artists

06/18/2014 09:42AM ● By Acl

'Brandywine at Twin Bridges' (1953), a tempera on panel by John McCoy.

By John Chambless

Staff Writer

"The Lure of the Brandywine," which opened at the Brandywine Museum of Art on June 6, ties together -- as perhaps no other exhibition has -- the intertwined relationship of Chester County, its history, its artists and the monumental effort it takes to heal and preserve the land.

There would be no legacy of artists in Chester County if not for the beauty of its open spaces, which drew Howard Pyle and his students, and later N.C. Wyeth and his family, to this area. The Brandywine Conservancy's efforts to keep that land open for generations to enjoy is what continues to draw visitors and inspire artists today.

"Lure of the Brandywine" looks at some familiar and not-so-familiar artworks in the context of conservation efforts in the region. That might sound like a classroom lecture, but the exhibit is a fresh and exciting way of looking at art and seeing beyond its pretty appearance.

"The Farm" (circa 1930), by Leal Mack, is more than a lovely N.C. Wyeth-like view of a barn,

cows and autumn trees. The eroded stream bank in the foreground is an example of the soil loss that the Conservancy works to prevent. A more direct tie-in is N.C. Wyeth's untitled painting of a farmer plowing a hillside, showing how farming was done in 1907. Its text panel points out how new methods of farming are being promoted to help preserve the county's remaining farmlands.

Carl Weber's "Cows Wading at Sunset" isn't just a luminous view of a placid stream and cows cooling their hooves. The text panel explains how letting livestock into streams can be prevented with fencing to protect the water source.

William T. Richards perfectly captures glorious summer light and clouds in two 1800s farm views, "A Farm in Chester County" and "The Springhouse." Karl Kuerner's 1992 "First Cutting" draws a connecting link between his family's farm and Andrew Wyeth's immortal works created at the property, which the Conservancy acquired in 1999.

"The New Fence" (1936) is a surprising Andrew Wyeth oil on canvas, strikingly bright and contemporary looking. It glows with intense sunlight, cool barn shadow and a vivid red bandana in the fence builder's pocket.

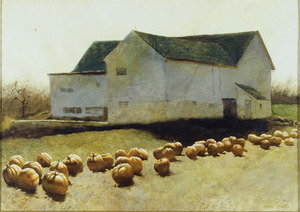

Jamie Wyeth's "Pumpkin March" shows Woodward Farm, which was developed in the 1980s in

cooperation with the Conservancy to limit housing sprawl.

Looking to the past, Clifford Ashley was a fellow student with N.C. Wyeth, and his bright oil, "Across the Creek at Rising Sun" (1919) captures Walker's Mill and its surrounding buildings -- a scene now vanished.

George Cope's 1904 oil, "Trout in the Brandywine," is a natural choice for the section of the show titled "Enhancing Water Quality," and Frank Schoonover's "Woods at Lafayette's Headquarters" (1898) is a beautifully painted oil of dappled sunlight filtered through leafy boughs.

Fox hunting -- and the estate owners who work for preservation of open space -- are represented by Charles Morris Young's "Going Home" (1922), showing a hunting party on Androssan Farm, the estate of Robert Montgomery Scott on the Main Line.

Another surprising Andrew Wyeth work is "Frog Hunters" (1941), an early tempera that captures the plant life of a swamp near his Chadds Ford studio. Anyone who's strolled the path along the Brandywine near the museum in Chadds Ford will recognize the sycamore tree that still hangs way out over the water in Andrew Wyeth's "Along the Brandywine Stream, Study for Summer Freshet," a dramatic 1942 watercolor.

Viewers will also recognize the motifs -- gnarled sycamore tree and a farm in the valley -- in Frank Delle Donne's "Landscape With Tree," but the artist will be much less familiar. The large oil synthesizes the styles and subject matter of both N.C. and Andrew Wyeth.

The Wyeth family's close relationship to nature is seen in Jamie Wyeth's "Purple Martin" and "Brandywine Raven," as well as Henriette Wyeth's "Hepaticas" (1966), a richly detailed oil of a forest floor; and Andrew Wyeth's "Garland" (1995) and "Buttonwood Leaf" (1981), which achieves his trademark microscopic detail in watercolor.

Carolyn Wyeth's "Blackberries" (1968) is a dense tangle of gleaming fruit and dangerous barbed wire that beckons the viewer with tiny rewards while keeping us away with the threat of injury.

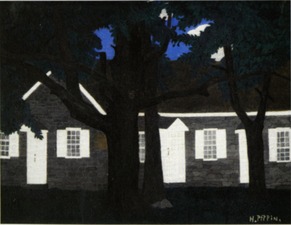

In the "Protecting Historic Structures" section of the exhibit, there's Cope's Bridge by George Cope, a structure that has been saved -- along with the nearby land -- by the National Register of Historic Places and the Conservancy. Big Bend -- the home of Conservancy founding member George Weymouth -- is seen in his well-known "The Way Back." Lafayette's Headquarters, seen in N.C. Wyeth's 1919 "Buttonwood Farm," is majestically situated among brilliantly lit sycamores, while the Birmingham Meeting House is captured in the dark, flat style of celebrated folk artist Horace Pippin.

Andrew Wyeth's 1943 tempera, "Osborne Hill," is a grand -- and grim -- vista of the hills and valleys of Chadds Ford as they would have appeared during the Battle of Brandywine.

Nearby, several display cases hold publications and examples of the works of the Conservancy, summing up the point that Chester County's art and its resources go hand in hand.

"Lure of the Brandywine: A Story of Land Conservation and Artistic Inspiration" continues at the Brandywine Museum of Art (Route 1, Chadds Ford) through Aug. 10. Call 610-388-2700 or visit www.brandywine.org.