The Heroin Crisis: Part 1 of a series

08/15/2013 11:39AM ● By Acl

By Richard L. Gaw

Staff Writer

Heroin has a new face. Where once its abuse was documented in horrific photographs of strung-out junkies, today it's in the hands of young people who play sports, excel in the classroom, and earn high praise from their colleagues at work.

It also has a different home. Once confined to the inner cities, it has infiltrated small towns and schools. It has arrived in southern Chester County by way of the I-95 corridor and nearby Wilmington and Philadelphia. A dose of heroin can be purchased nearly anywhere for as little as $5.

What's happening here is part of an epidemic in America. Between 1995 and 2002, the number of our nation's teenagers who have admitted to using heroin at one point in their young lives increased 300 percent. The availability of high-purity heroin makes snorting or smoking it viable options, instead of just injecting it.

Beginning in this issue, and continuing in our Aug. 21 and 28 editions, we will examine the presence of heroin in southern Chester County, as told by those whose lives have been affected by addiction, those who are helping to heal and educate, and those who are trying to prevent it from reaching our neighborhoods and our schools.

In the first part of this series, we meet 22-year-old Timmy, a resident of New London Township, who fought a heroin addiction for three years. Through his courage and the guidance of his parents, he is once again working on living a normal life. Their names have been changed in the story to protect their anonymity.

--

To look at Timmy, a resident of New London, is to dispel the preconceived notion that heroin addicts are the living and breathing embodiment of skeletons.

He is 22 years old, and his eyes are clear, his smile is quick, and his body is chiseled from working at his father's contracting business, and although he occasionally sprinkles his sentences with the language of the streets, his answers are razor sharp and direct. He defies the photographs seen in magazines and newspapers over the past several decades, those depicting the back alley hell of dealers, dope and degradation.

Hopelessness, as he begins to tell his story, is beginning to fade from Timmy's life, and is being replaced by a slow re-emergence from the addiction that threatened to consume him. As he speaks, his mother Anna listens. She is the Greek Chorus of Timmy's story, the sidebar backdrop to the horrific tumbledown of her son's addiction, and the blooming orchids of his recovery...

Timmy was born in Delaware County, but when he was a very young boy, the family moved to southern Chester County. As a kid, he played Pee Wee football, Little League baseball, rode skateboards, and by the time he was 12, he was helping out his father at the family business. Anna has two sons of her own from a previous marriage and married Timmy's father when Timmy was three. The fact that she is not Timmy's biological mother means nothing to her; when she married Bill, love was a package deal, and together with her two boys and his two boys, they raised a family.

"Growing up, Timmy was happy-go-lucky, affectionate and easy to please," Anna said. "He has always been a “ladies man” and the kind of kid who made friends very easily.”

By the time he reached middle school, the childhood world of games and bicycles that Timmy had grown up with had been replaced by visits to cornfields with his buddies. Marijuana was a weekend thing, just something to make life more interesting. They'd get high in the cornfields around West Grove, knock back a few beers, in a constant quest to accelerate their life from the small town world they had grown up in, to a place that offered them an invented and temporary limelight.

No Big Deal

"When you're in elementary school, you're a kid, but when you're in middle school, you're no longer a kid," Timmy said. "By the time I'd reached middle school, I went in a million different directions. School dances got old very quickly. Pot and Molly (a form of the drug Ecstacy) were so easy to get in middle school. Everybody was doing it. It was really no big deal."

At Avon Grove High School, Timmy was a two-way player on the school's football team -- a guard on offense and a linebacker on defense. In order to remain on the team, he needed to keep up his grades, and he did, even making the honor roll a few times. He thought he was exactly where he needed to be: athletic and popular with decent grades. He still smoked weed and drank beer, and even though he'd heard of hard drugs creeping about, he stayed clear of them.

At the end of his sophomore year, he was suspended for playing a harmless prank in the school cafeteria. As part of the punishment, he was thrown off the football team, and now that he didn't have the academic checks and balances that playing sports in high school demands, Timmy went in a different direction.

"I saw a split in friends with Timmy," Anna said. "I kind of knew that something was going on but wasn’t sure what. We had preached to our children since they were younger to stay away from drugs and alcohol. We set examples. We'd talk about so-and-so, who got arrested or who was killed and risky behavior. You're never thinking as a parent that this could happen to your son or your family."

Sam, Timmy's older brother, is vehemently anti-drug, but Pete, the oldest, had spiraled slowly out of control from drugs, and behind him, Timmy followed. He started hanging with a rougher crowd. He used his fists to settle arguments that occurred in the school. The free time he now had was like being untethered from a chain, and when he was 15, he began to get high on cocaine wherever he could find it. He said it was everywhere -- at house parties and in empty barns filled with teenagers.

"I pretty much knew not to do it but I did it anyway," Timmy said. "My parents never knew any of the stuff I was doing. The classification of heavy drugs has changed. Cocaine was so easy to get. Avon Grove's got a bunch of rich kids, so buying coke wasn't any big deal."

Serious Business

He transferred to Oxford High School in his junior year. There, he found that the approach to the use of drugs was more intense than it was in West Grove. In Oxford, partying took on a purpose and a personality driven by the Molly, the weed, the coke, the pills and the massive amounts of alcohol that Timmy saw at parties. This was no weekend thing out here, he saw. This was serious business, and he dove right in. He'd obtain drugs, free of charge, from people he'd meet up with at parties. He'd be guided into school bathrooms, where he'd do coke and pills like Oxycontin and Percoset. By the time he'd reached his senior year at Oxford, he was dropping pills every day.

"It wasn't rebellion, it was just there, a curiosity," Timmy said. "I've always been the kind of person who's been curious."

He tried heroin only once in high school. A kid from his art class referred to the contents of the blue wax bag he held before Timmy as "dope." He gave the bag to Timmy, free, who promptly took it to the bathroom and snorted it. Soon after, he became ill while eating his lunch in the school cafeteria.

"It made me sick to my stomach," he said. "I couldn't understand why anyone would ever do something like that. The word 'heroin' itself is just a nasty word. It's weird the way you get introduced to it. It puts a cloak over itself and re-invents itself. When we were kids, we knew it was the worst thing in the world, but it was my own curiosity, my own stupidity."

Timmy was a senior in high school and was already in the process of killing the myth of the drug abuser. With every pill swallowed and every new drug attempted, he was burying every stereotype. He didn't look strung out. He was still managing to attend classes. He was still working at his father's business. He had everything he needed in life and more. "I never liked those stereotypes, that drug addicts come from broken homes or impoverished backgrounds," Timmy said. "It doesn't matter where you're from or what background you have, if you have the inclination to become addicted, none of that matters."

But after he graduated from Oxford, the rabbit hole of his life was two steps away, and he was about to fall off the cliff.

"When they get to be a certain age, they're not with you all the time," Anna said. "He's out there making his own decisions. The only thing I can hope for is that he's out there making the right decisions. But you're never guaranteed everything. People suffering from addiction are extremely good at lying and living the 'secret life.'”

One weekend, he and his buddies couldn't find any Percoset or Oxycontin. Someone suggested they score heroin. They went out to find it, came back to where they were partying, "and it was like, 'Why not?'" Timmy said.

Into Outer Space

He said the sensation was like that of an instant rush, the physical and mental parts of himself speeding to the pleasure zone of his body in an effort to get there first. Once there, it was like exploding in a warm sense of euphoria, like laying in a bed of nothing but feathers, and melting into himself. Coke, he said, will get you amped up. Crystal meth will keep you up for days. Pot will bring you down to a two-dimensional world, but heroin will send you nodding somewhere into outer space.

"Heroin is a really weird drug," Timmy said. "It comes on in waves. It had its hooks in me from the beginning. I did it one day and the next thing I knew, it had turned into an everyday thing. I realized it was overtaking my life right away. As soon as you find yourself doing it on an everyday basis, you see your life as a daily cycle, and then there is the dependability, and soon you realize that you can't go through the day without it.

"I was awake but in my own world...and I simply disconnected."

He was 19 years old.

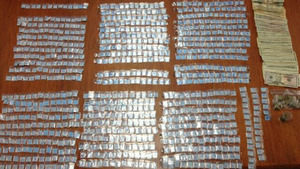

For the next two years, Timmy hid from his family. He hid everything; his addiction, his life, who he was, the roadblock formation of life that is usually so coherent and alive when a young person evolves in their early twenties from the person they are to the person they want to be. Heroin was everywhere like candy throughout southern Chester County, and if he had any problem, Wilmington was a stone's throw away, and Philadelphia was less than an hour away. In fact, the entire I-95 corridor was the moveable feast of drugs. He didn't need to dip into his savings for a fix, either; heroin was about five bucks a pop, for which the buyer received a dose of white powder enclosed in a blue wax packet, and there were stamped names imprinted on them, too.

What may have begun to save him was that he got sloppy. He hadn't hidden everything because he was not thinking properly due to his addiction. Anna and Bill felt like they were losing touch with their son, that he was becoming someone they didn’t know anymore – a stranger. One day, they entered his room while he was away. The little blue bags were all over the room. Anna scanned the Internet in an attempt to find out what the bags were.

"Do you have a problem?" they asked Timmy later that evening.

"No," was all they heard. "What were you doing in my room?"

Leaving Home

In the summer of 2011, Anna and Bill went to his room again. They found more blue bags. Now knowing what the bags contained, they confronted him, and gave him two options. Either he go to rehab, or leave their home. At the same time, they were telling Pete the same thing. Pete went into rehab. Timmy left home.

"We were devastated, we were sick," Anna said. "But he was 20. He told us that we couldn't tell him what to do with his life. He told us that he was a man now. We agreed that he was an adult, but he was living under our roof and we told him that if he didn’t seek help that he couldn’t live in our home anymore. So he left home and there was nothing we could do about it.

"There is a shame factor," Anna said. "You don't want to go telling people, 'Hey, my kid's a junkie.' You want to help your kid, but you don't want to put it out there. We wanted to help Pete and Timmy, but we didn't know which way to turn."

Timmy made an effort to control his heroin use. He began attending a Suboxone clinic as an outpatient near where he now lived with a friend. He was there for four months, and for him, the whole purpose of the clinic was to exchange one addiction for another. "The whole place was a joke," he said. But it worked. He was now clean and remained so for about three months.

During his slow road to recovery, he'd heard that a good friend of his from Avon Grove, someone he grew up with, had recently died from a heroin overdose. Within days, Timmy had relapsed. He didn't care anymore. Why? If heroin took his friend, he thought, what was the point in his remaining clean?

“It was another clear indication that this drug takes away all reasoning from the addict,” Anna said.

Rock Bottom

Timmy didn't have a fear that this fix would be his last, nor was he able to pinpoint any one moment that would have been his rock bottom. "Heroin itself is a rock bottom," he said. "Once you start doing that drug, you're pretty much at rock bottom. The only thing worse is death."

Anna began playing games with rationality. When she found out that Pete and Timmy were using heroin, she found pens taken apart, straws of all kinds cut in two and those little blue bags throughout their bedrooms.

"I was stupid enough to say to my husband, 'Well, at least they're not injecting it," she said. "I kept saying, 'We need to convince Pete and Timmy to get help now, before it gets any worse.'"

Timmy got blood poisoning from a hypodermic needle. It was the last thing he wanted to do -- to

bang dope into his veins -- but he was already too far gone to care anymore. On the rare occasions he allowed himself to look at his face in a mirror, he could barely recognize any glimmer of hope in his reflection. The engine of his life -- the childhood dreams he had that were formulated in his emulation of his father -- were all shutting down. He was now 21 years old and knew absolutely nothing about himself. His very definition, all of its contours and ridges, was all held in the little blue bags, hundreds of them, now emptied of their contents.

On a Sunday in the spring of this year, after a nearly three-year addiction to heroin, Timmy visited his parents. "He sat us down and told us that he was sick and tired of being sick and tired," Anna said. "He told us that he didn't want to die, that too many of his friends' lives were cut short by heroin.

"He told us, 'I am tired of being in the dark.'

Together, Timmy and his parents talked about his options again. Then Timmy picked up the phone and called a rehabilitation center. Three years was long enough.

Recovery

For the next month, he attended the Malvern Institute in West Chester, and then spent the next two months living in a recovery house. "It was an eye opener going to rehab," Timmy said. "It's like the TV shows about people in jail for extended periods of time. Here I was, a young man in my early twenties, in meetings with people who are in their 50s and 60s, who've been addicts for decades. I kept thinking to myself, 'I'm glad I'm doing this now and getting it over with, because I don't want to be some old dude still struggling with addiction, being sent to rehab on some court order."

"We did not save Timmy. He saved himself," Anna said. "He reached out to us, even though we always kept that line of communication open. We knew that we could chase him to the ends of the earth, but if he wasn't ready, there was nothing we could do to make him get well. He had to want it. He had to be ready. And he was. Saving his life and choosing recovery was on account of his own free will."

This past June, Anna found the little blue bags in Pete's room again and, like they did with Timmy, Pete was given the same choice of going to rehab or leave home. Pete chose to leave, and they have not seen him for months. It kills Anna and Bill to not know where their oldest son is, but she said that she will not compromise Timmy's new-found sobriety with his older brother's abuse; she will not choose the weakness of one child over the strength of another. The cycle of addiction has got to end.

Meanwhile, Timmy attends meetings of heroin users. Most of them are as young as he is, some even younger. He speaks to them in their language. He tells them of his slow, horrible slide, his self-induced coma. He speaks about his three-year descent into the haze of addiction, of being in the dark. He tells them about his rise and how he’s starting to feel “normal” again.

"If someone who has found sobriety tries to help an addict who does not want help, they will get you high before you can ever get close to getting them clean," Timmy said. "I want to help others, but I can’t hurt myself by doing so. I know so much about what they're going through. You pay more attention to people who speak directly from their heart rather than books. I can’t help my own brother, he’s out there and there’s nothing that I can do about it. When I was 19, no one could tell me anything, but now..."

When Timmy was a little boy, his dreams were to be just like his father when he grew up, to someday work hard side-by-side with him at the family business. Now, each morning, he wakes up early and drives off, like so many 22-year-old young men, in pursuit of his childhood dream.

Coming next week: Dr. Alex Fernandez, of the Jennersville Hospital emergency department, is on the front line when drug abusers overdose.